What Canada’s Charter of Rights says, like the US Bill of Rights, is always subject to interpretation. And interpretations are always subject to debate and strong criticism of the court.

The Interpretation Method is Critical

Since the Charter came into force in 1982 numerous cases have been decided applying it. There are two schools of thought about how judges should interpret and apply the Charter of Rights, both described in metaphors. These two approaches often produce different, even opposite results, from the same constitution.

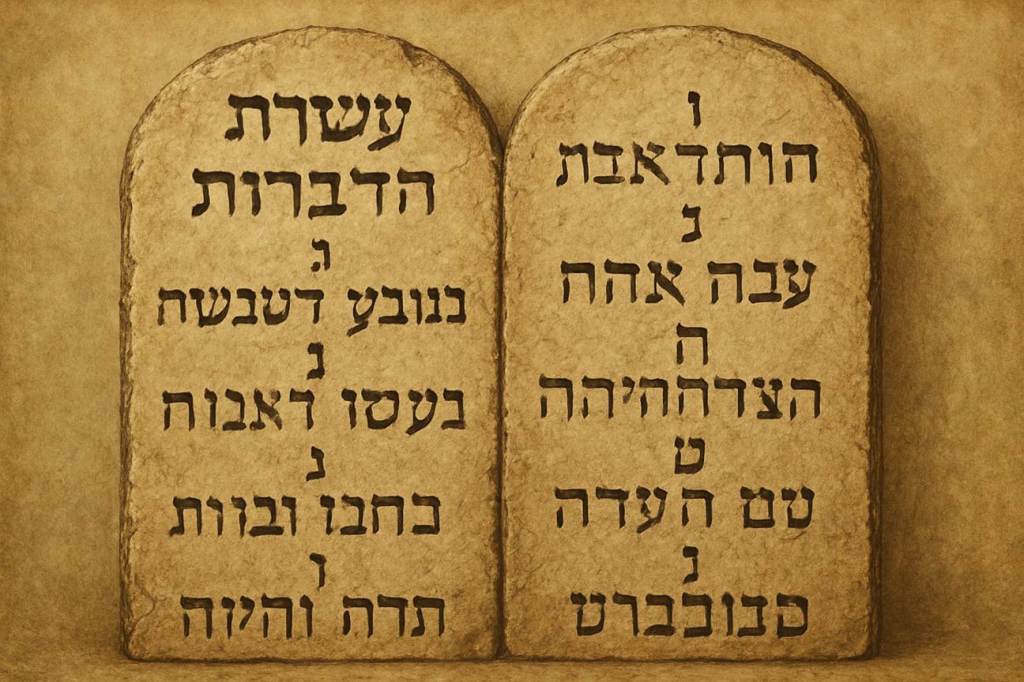

One approach, usually called “originalism” or “textualism”, I shall call the “tablets of stone” (recalling the 10 Commandments given to Moses on tablets of stone).

Image created by ChatGPT

The other is called the “living tree”.

Which method is used is important, particularly with the language of section 7, the right to “life, liberty and security of the person”.

The Tablets of Stone Approach

This is now the older view, but some judges still use this by focusing on the words as written and their history.

The 1985 BC Motor Vehicle Act case discussed the intentions of the Charter’s drafters. Some of the provincial politicians and public servants who had negotiated the Charter’s content were called as witnesses. But the Supreme Court of Canada decided not to rely on such evidence, as being subjective legislative history:

“… Statements made in the course of its drafting, whether by politicians or by civil servants, cannot be determinative of its meaning….”

Even without such evidence judges still use the tablets approach. A recent example is the strong dissent by Ontario Justice Miller in the Drover case, writing that section 7 was inextricably linked to state action in the administration of justice. The majority disagreed and followed the recent trend of applying section 7 to a wide-range of claims to equality and psychological security. Justice Miller warned:

[98] As well, abandoning the administration of justice requirement would produce the very concerns about overstepping the judicial role …. . Severed from their “inherent domain … as guardian of the justice system,” judges would be drawn into “the realm of general public policy”. There, they would be tasked with addressing “broader social, political and moral issues” about which personal choices are sufficiently fundamental. Because the law does not provide a determinate answer to these questions, they “are much better resolved in the political or legislative forum,” at least when they fall outside of the judiciary’s role as defender of the justice system.

The Living Tree Approach

The living tree metaphor sees Charter rights as flexible and capable of evolving with society. This is now the more common approach, although how flexible it is in practice varies with the issues before the court.

Which Approach is Better?

Each interpretation approach has advantages, but also serious weaknesses. The underlying issues are: when should judges make law, and how much flexibility is too much? The debate is often worded in simplistic, unhelpful slogans like: “Let’s not have “activist judges” with expansive new interpretations of our constitution”. OK, but what’s an activist judge? One who made a decision I didn’t like?

Or: “Let’s not have provincial premiers who disrespect the constitutional rights of citizens by using the notwithstanding clause” (section 33)? OK, but when did a premier show such disrespect? The last time that province’s law was disrespected by an activist judge?

Instead of slogans, let’s assess each of these approaches.

The Arguments For and Against the Tablets of Stone Approach

The “for” argument starts with the premise that the authors of the Charter said what they meant and meant what they said, a reasonable assumption.

The metaphor of the ‘tablets of stone’ suggests constitutional protections should be immune to the shifting winds of political or social fashion. Ancient legal codes, such as the Ten Commandments in the Bible, reflect this mindset: the law is meant to endure, a fixed moral compass guiding human behavior.

The U.S. Constitution was adopted in 1787. Its Bill of Rights guarantees protections of speech, religion and due process, intended as immutable safeguards. This rigidity provides stability and predictability, but societies evolve. What made sense two centuries ago in the USA, or even half a century ago in Canada, may no longer reflect contemporary circumstances.

Issues such as digital privacy, reproductive rights, or same-sex marriage were inconceivable to the framers of the U.S. Constitution or Canada’s Charter, yet modern societies demand legal frameworks to address such current issues. Amending a rigid constitution is almost impossible. In the U.S., only 27 of thousands of proposed amendments have succeeded in over 230 years.

Canada’s Charter, although younger, contains elements resembling tablets of stone. However, the section 7 rights to life, liberty, and security of the person are expressed in aspirational, very general language. They are like a semantic Rorschach test, the interpretation of which is in the eye of the beholder. They raise obvious interpretative questions: how much liberty; and liberty to do what, to whom? Is security of the person physical, psychological, financial or more, such as the right to ride a bicycle in safety down a bike lane on University Avenue in Toronto, as was held in a recent case?

These vaguely worded section 7 rights must be interpreted in specific cases. Remember, it wasn’t “activist judges” who drafted section 7 (and some other sections) to be this vague, it was politicians.

The Arguments For and Against the Living Tree Approach

The living tree concept is that our constitution is capable of growth, adaptation, and development over time. Judges should interpret constitutional provisions in light of contemporary social norms, technological changes, and evolving understandings of justice.

Yet flexibility also carries risks. The branches of a living tree (see photo above) do not necessarily grow evenly around the tree. If all the branches grow on one side, that’s because judicial interpretation consistently favors one ideology, meaning that the tree may lean to the left or lean to the right. Above is my photo of a living tree, an arbutus, that grows out of the rocks near my house. The tree appears to be leaning to the left. It is actually growing towards the south, for the sunlight. I took this photo from the east side of the tree. Had it been taken from the west side it would have appeared to be leaning to the right. This illustrates an important principle: whether the living tree leans to the left or the right depends on your point of view.

Flexibility also creates uncertainty. If the boundaries of human rights constantly evolve, citizens and governments may struggle to understand their rights and obligations. Stability and predictability, the virtues of the tablets of stone approach, can be negated.

The Necessity of Interpretation of Imperfect Constitutions

Both models are complicated by the inherent vagueness of constitutional language. Phrases like ‘liberty and security of the person’ or ‘equality before and under the law’ are morally resonant but legally ambiguous. They raise questions that cannot be answered by reading the text alone. That is not the fault of judges, nor of constitutional drafters. The reality is that every constitution is necessarily brief and vague. So pick your trade-off.

The tablets-of-stone approach may freeze vague language into law, creating conflicts between timeless generalities and evolving realities. The living-tree approach allows greater flexibility but opens the door to interpretations shaped by currently trendy judicial or societal bias.

Who Should Make Law: Governments or Judges?

Judges admit that when they create new interpretations of the constitution, they are, in that limited sense, making law. That’s inevitable if their constitutional decisions change anything. On the other hand, if governments knowingly enact unconstitutional laws, just to appeal to the party base, they invite and probably intend the courts to over-rule them.

The Silent Conversation Between the Politicians and the Judiciary

In elections a small minority of voters shifting between political parties can make the difference between being the elected government or being the opposition. On contentious issues like abortion or same-sex marriage politicians have been reluctant to enact popular legislation because a strongly opposed minority might vote them out. They leave it to the judiciary to make these controversial decisions on the theory that ‘you don’t have to worry about getting re-elected, we do’. Governments will finally, with some theatrical reluctance, enact the law that the judges have required.

Conclusion

Canada’s Charter, like all constitutions, embodies both good intentions and vague language. Its effectiveness depends not on perfect wording but on the ongoing conversation between judges and legislators. There is no perfect decision-maker, no clear constitution, no right balance. We can only choose which imperfections we are willing to accept, and live with the consequences.

Discover more from Andrew's Views

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Categories: Charter of Rights, democracy, Government, Judges, Law, Parliament, Supreme Court, Uncategorized, US

Thoughtful presentation. Thank you. I especially liked the discussion of your arbutus tree.

I wonder if it’s really true that digital privacy, same-sex marriage, and reproductive rights were unknown to America’s Founding Fathers.

Private papers were familiar, as being secure against unlawful seizure and infringement on freedom of speech and of the press. Reading another man’s mail was so ungentlemanly that military and diplomatic codebreaking was resisted by traditionalists long before digital encryption techniques developed. Fortunately their junior maths whizzes were doing it already behind their backs.

At least one President in the early 19th century was probably homosexual and lived openly with a man, though not in the White House. Even if the idea that marriage could include such unions was incomprehensible, the facts underlying it were not. And what were the traditions of the Royal Navy if not rum, sodomy, and the lash, albeit the second punishable by hanging….even if Churchill never actually said that.

The Hippocratic Oath ca. 300 BC forbids the giving of a “pessary” (probably not the same meaning as today) to procure abortion. This is almost certainly out of concern that the mother would die from the attempt, not out of concern for the fetus as it is sometimes interpreted today. Pregnant women have been trying to separate themselves from their unborn children ever since. I’d have to look up when abortion was first criminalized but I’d be surprised if it wasn’t as soon as methods developed that required a skilled accomplice.

Leslie MacMillan

Hamilton, Ontario

LikeLike

The Swiss system for referendums seems to have merit. The existing constitution operates in tablet mode. It can be modified by referendums which are conducted under restrictive time limits and expenditure limits.

If a referendum passes, the tablet is modified for a period of a minimum of ten years. At that point, if there is considerable dissatisfaction with the new tablet, an effort can be made to modify or cancel the earlier referendum.

This system has the merit of the Swiss constitution being transparent, understandable, and predictable to its citizens when it is operating in tablet mode. Yet, it is capable of being amended over time in an orderly way which reflects broad support from the majority of its citizens.

This model seems to have served Switzerland well, producing long term social harmony and effective governance.

Perhaps in Canada we should consider adopting the Swiss model, since our present Canadian Constitution and Bill of Rights is giving us neither social harmony nor good governance. Instead, it seems to be fostering more division and poor governance the longer it remains in place.

LikeLike